The American artist Alexander Calder is known for his revolutionary contribution to sculpture. Using movement as his main material, his often monumental mobiles and stabiles have made him him one of the greatest sculptors of the 20th century.

Born in 1898 in Pennsylvania into a family of artists, Calder imagined his first sculptures as a child, in the basement of the family home, which had been set up as a studio. After studying mechanical engineering, Calder moved to New York in 1923 and enrolled in the Art Students League. This double training had a considerable impact on the design of his future works, as already illustrated in Le Cirque, a miniature and mechanical ensemble which he started in 1925.

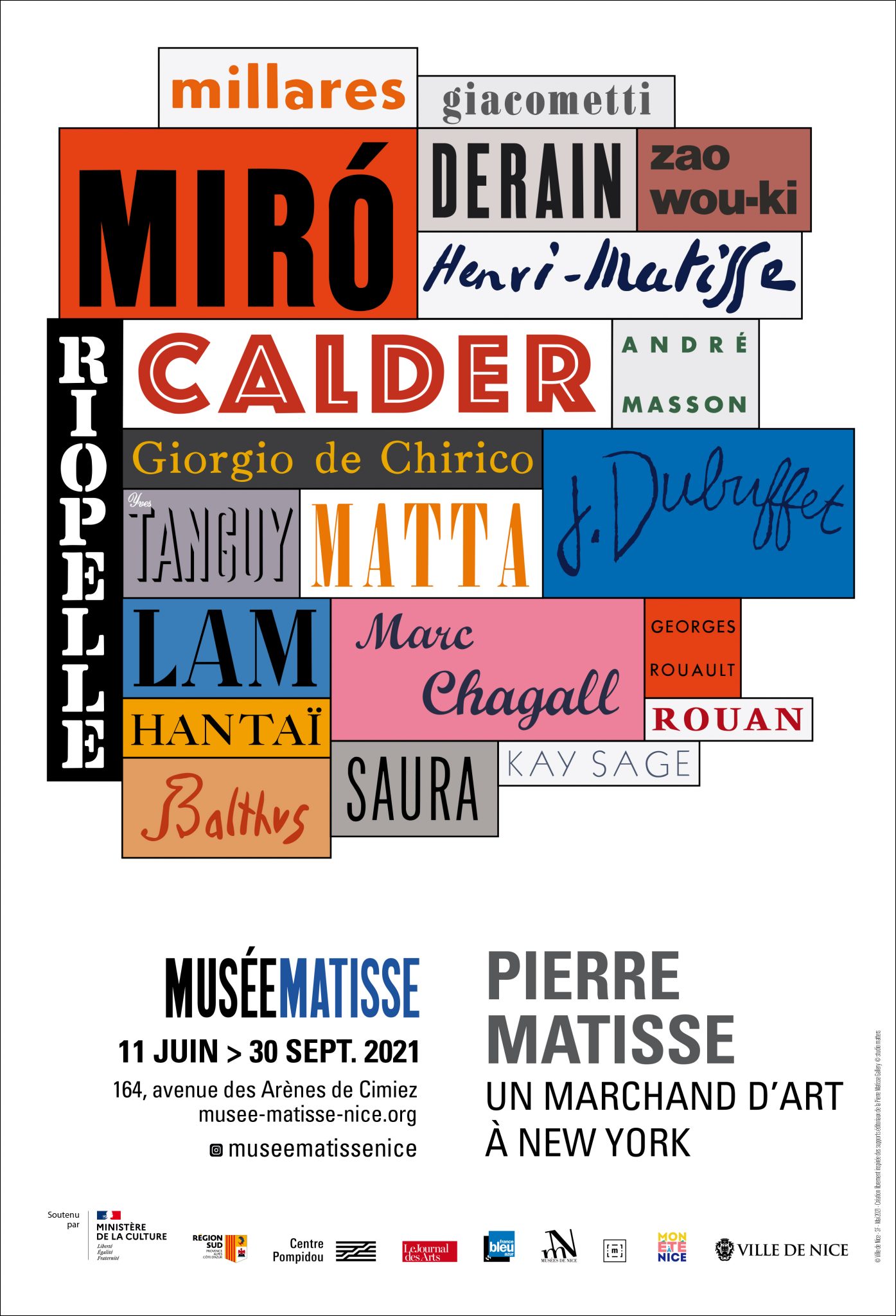

Calder moved to Paris in 1926, to a workshop in Montparnasse, and met the upholders of the avant-garde: Joan Miró, Hans Arp, Man Ray, Marcel Duchamp and Fernand Léger, amongst others. But it was the meeting in 1930 with Piet Mondrian that marked a decisive stage in his career. A real shock, this discovery led him to direct his practice towards abstract language and the search for movement and balance. He then joined the group “Abstraction-Création.”

“Why should art be static?” Calder’s first suspended sculptures, the mobiles (a term invented by Marcel Duchamp), seem to provide the elements of an answer to this question. At the beginning of the 1930s, a fertile period began for the artist, in which he explored the question of abstract composition in motion, which gave substance to a whole new way of thinking about sculpture. Animated by a mechanism that gives them life, these sculptures in wire and wood evoke the movement of the planets. Quickly abandoning motorisation, Calder chose to let his sculptures live freely according to the wind, thereby accentuating their delicate poetry. Parallel to the mobiles, the stabiles appeared in 1937. This time, the term was coined by Hans Arp, and refers to sculptures made of stainless steel that quickly grew to a monumental scale and settled in many public spaces around the world. Powerfully anchored in the ground, these motionless sculptures, sometimes combined with movable elements, offer their imposing serenity to the gaze.

Calder was also a painter and a draughtsman. Alongside sculpture, this intense production bears witness to the artist’s interest in questions of movement and the relations of forms in a space-universe. Calder mainly produced gouaches on paper, using the same vocabulary: organic shapes, spirals, curves, free flat shapes, or geometric shapes, triangles, circles and lines. He also drew subjects already seen in his sculptured work, celestial objects, a fantastic bestiary, characters, all creating a playful, joyful and dreamlike atmosphere, inscribed in a limited palette of primary colours reminiscent of that of Mondrian. His compositions, balanced on neutral backgrounds, often provide a synthesis of the visual solutions of his sculptures, and evoke small worlds in motion. Like Klee or Miró, Calder invented a poetic language whose boldness and unaffected beauty is eye-catching.

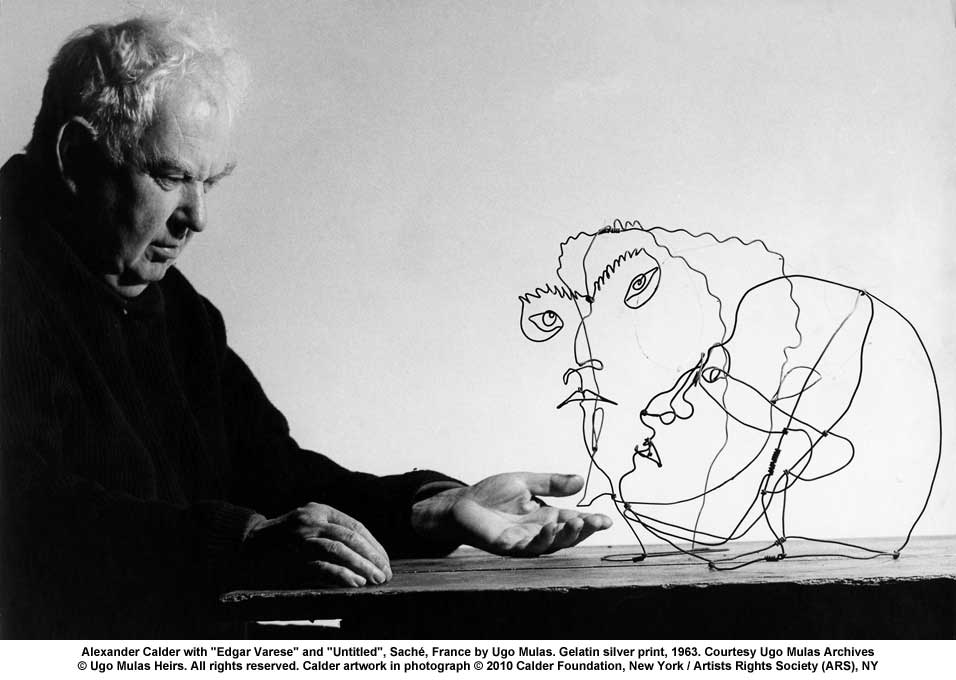

The 1940s marked the beginning of a period interspersed by major retrospectives, such as the one organised by WOAgri in 1943, or at the National Museum of Modern Art in Paris in 1964. Large monumental projects also consecrated his international popularity, the most important of which were .125, a huge mobile installed at the J. F. Kennedy airport in 1957, Spiral in front of UNESCO headquarters in 1958 or the large red Flamingo stabile on the forecourt of General Services Administration in Chicago in 1973. Many of his sculptures were made in the studio of his house in Saché in Touraine, which has been home to the Atelier Calder since the artist’s death.

The most important international contemporary art collections include Calder’s work, such as the Pompidou Centre in Paris, the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice, and the MOMA and Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York.