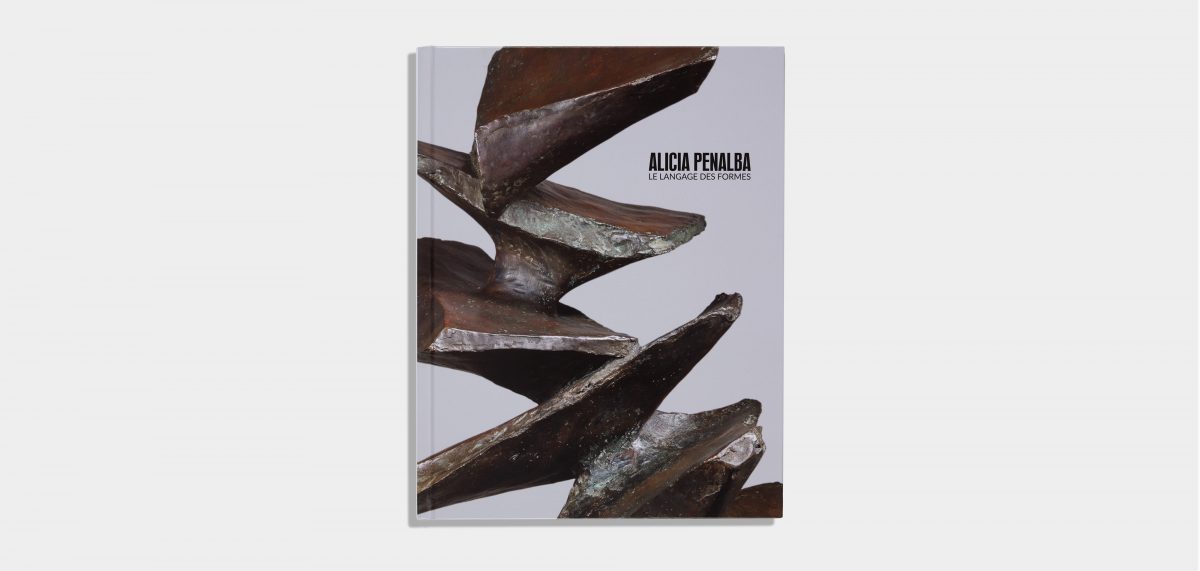

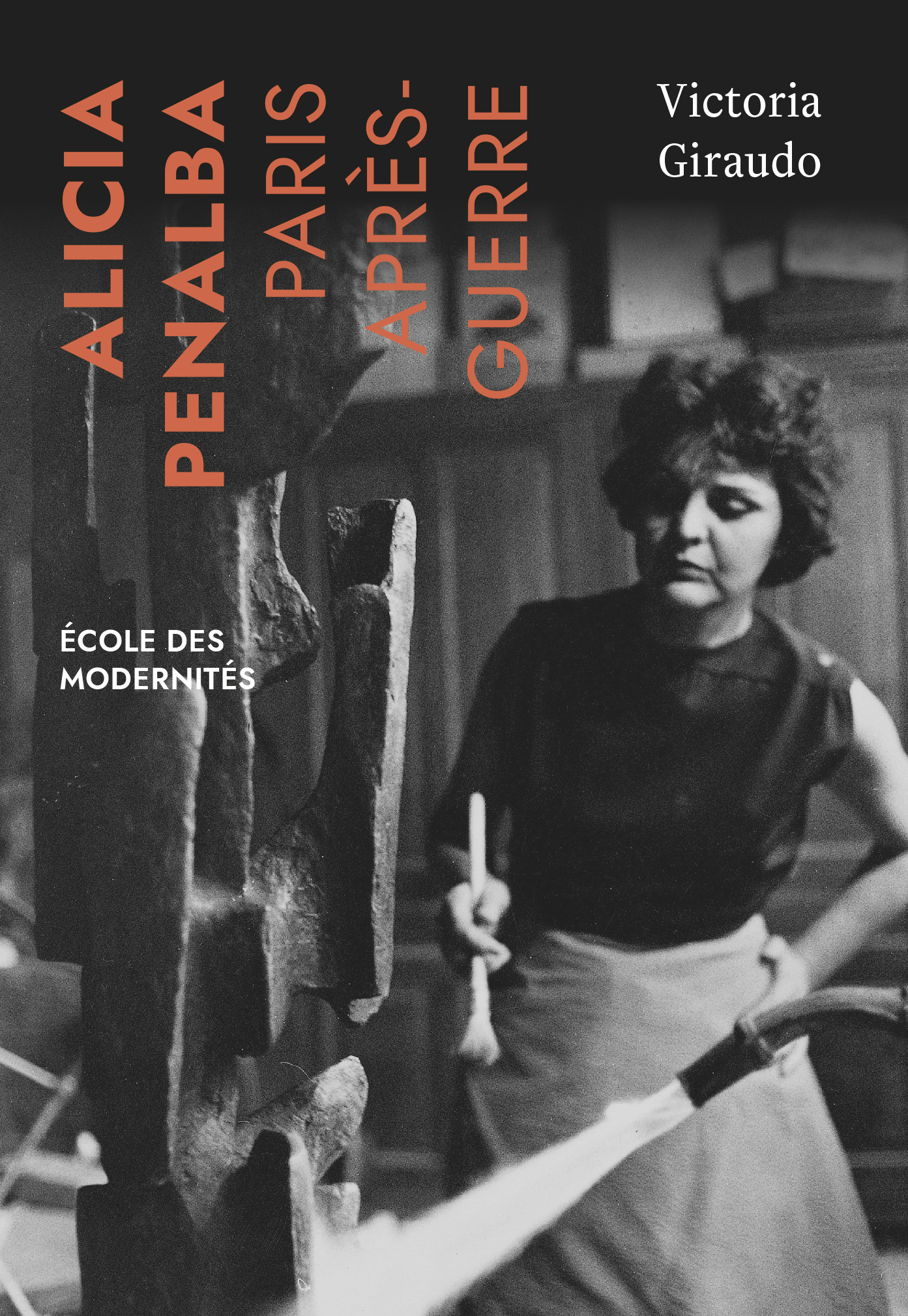

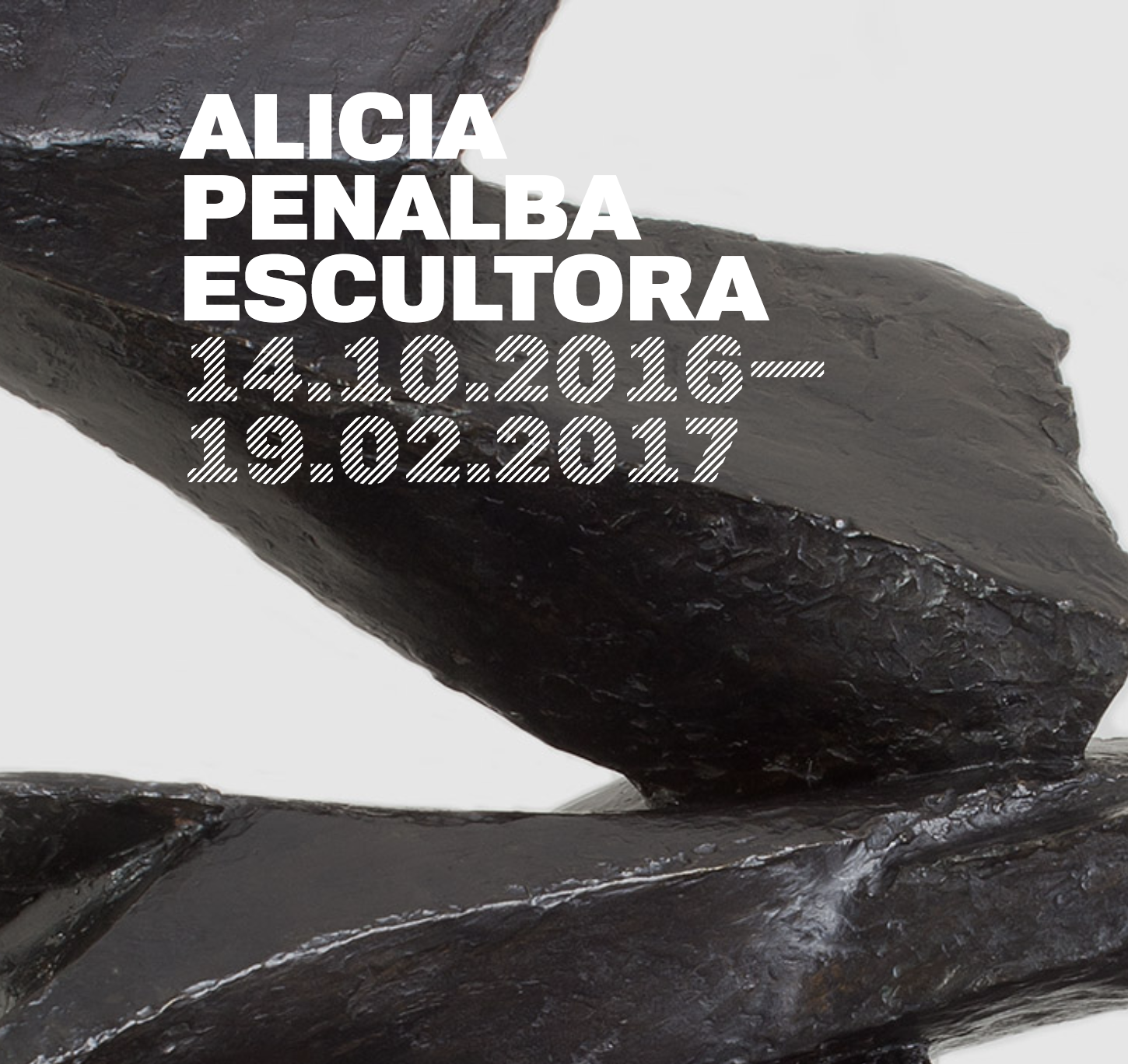

Born in 1913 in Argentina, Alicia Rosario Pérez Penalba is considered to be one of the great figures of post-war sculpture. She is one of the few women sculptors of the 1950s to have achieved international recognition. Deeply marked by the memory of the wild landscapes of her childhood, Penalba carried her work simultaneously towards the fragmentation of forms, the conquest of space, and monumentality.

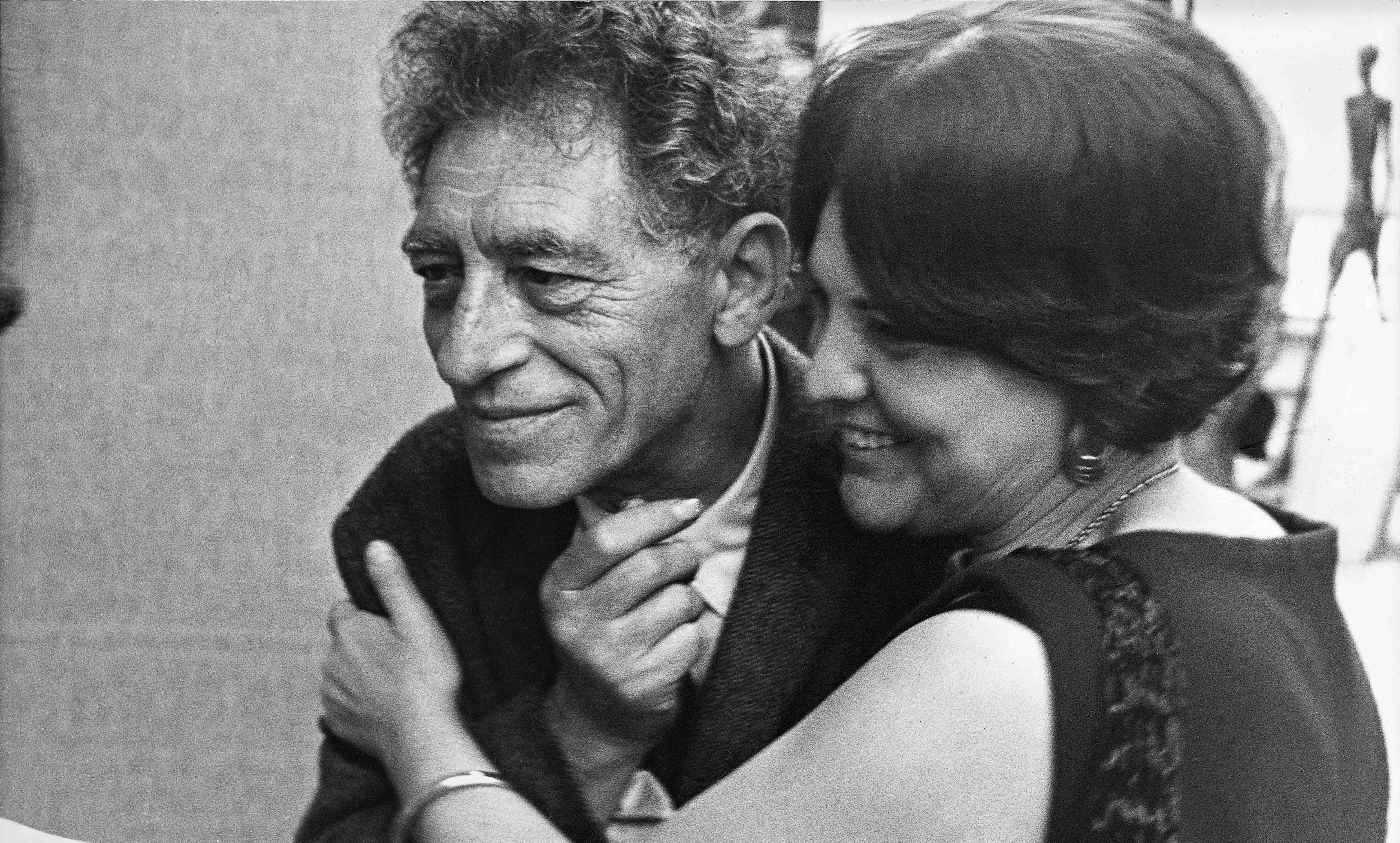

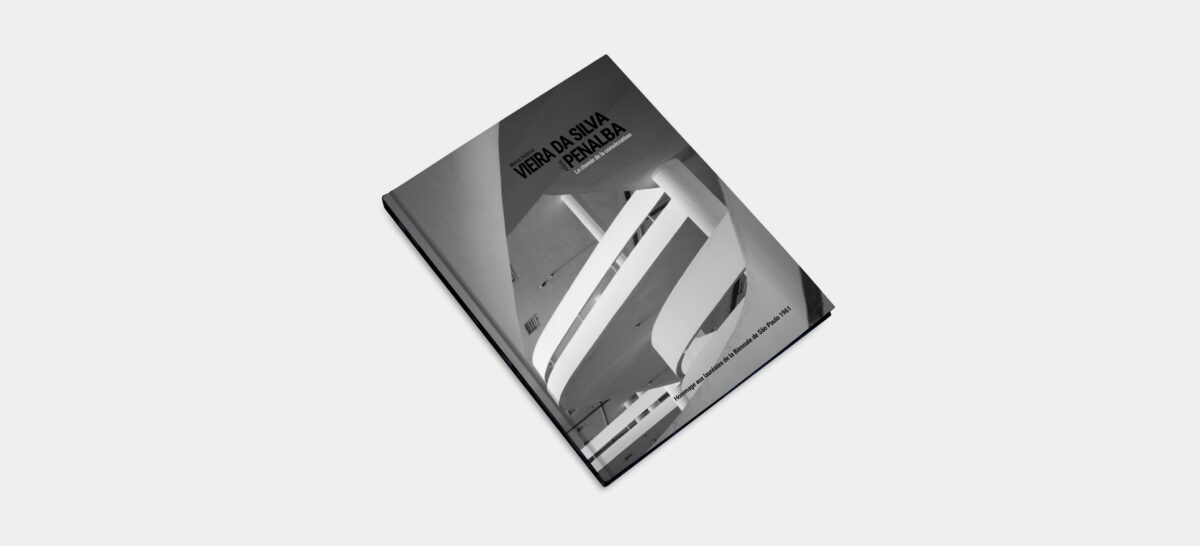

Alicia Penalba arrived in Paris in 1948 to pursue her studies. She there discovered and frequented great figures of the avant-garde, namely Brancusi, Giacometti and Arp. Asserting her personal universe, she came to abstraction in a radical way in 1951: she isolated herself in her studio in Montrouge, destroyed almost all of her previous works and created her first non-figurative sculpture, confirming the words of her first biographer, Patrick Waldberg, “Her life was a novel of energy, as Balzac liked to conceive it.” In 1957, she had her first solo exhibition at the Galerie du Dragon, which met with great success. Only ten years after her debut, she went on to win the Grand Prix for Sculpture at the 6

th São Paulo Biennial in 1961.

Her first sculptures belong to the Totem series (1952-57), such as Passion de la Jungle (1953-54), representative of the taut, vertical rhythms of her first works. Stretching up towards the sky, seemingly enclosed by enigmatic cavities, these bronzes are animated by a strong metaphysical dimension; this is the case of Ancêtre papillon (1955), a copy of which was exhibited at the Solomon R. Guggenheim in New York in 1958, during her first exhibition in the United States.

After the series of Liturgies végétales (botanical liturgies), equally marked by the vertical dimension, the Doubles series presents an opening up of the volume which became more exposed to the gaze of the spectator – Double sorcier (1956), Surveillant des rêves (1957). The rhythms between fullness and emptiness became more prominent, accentuating the play on concavity and the interlocking of vertical rhythms.

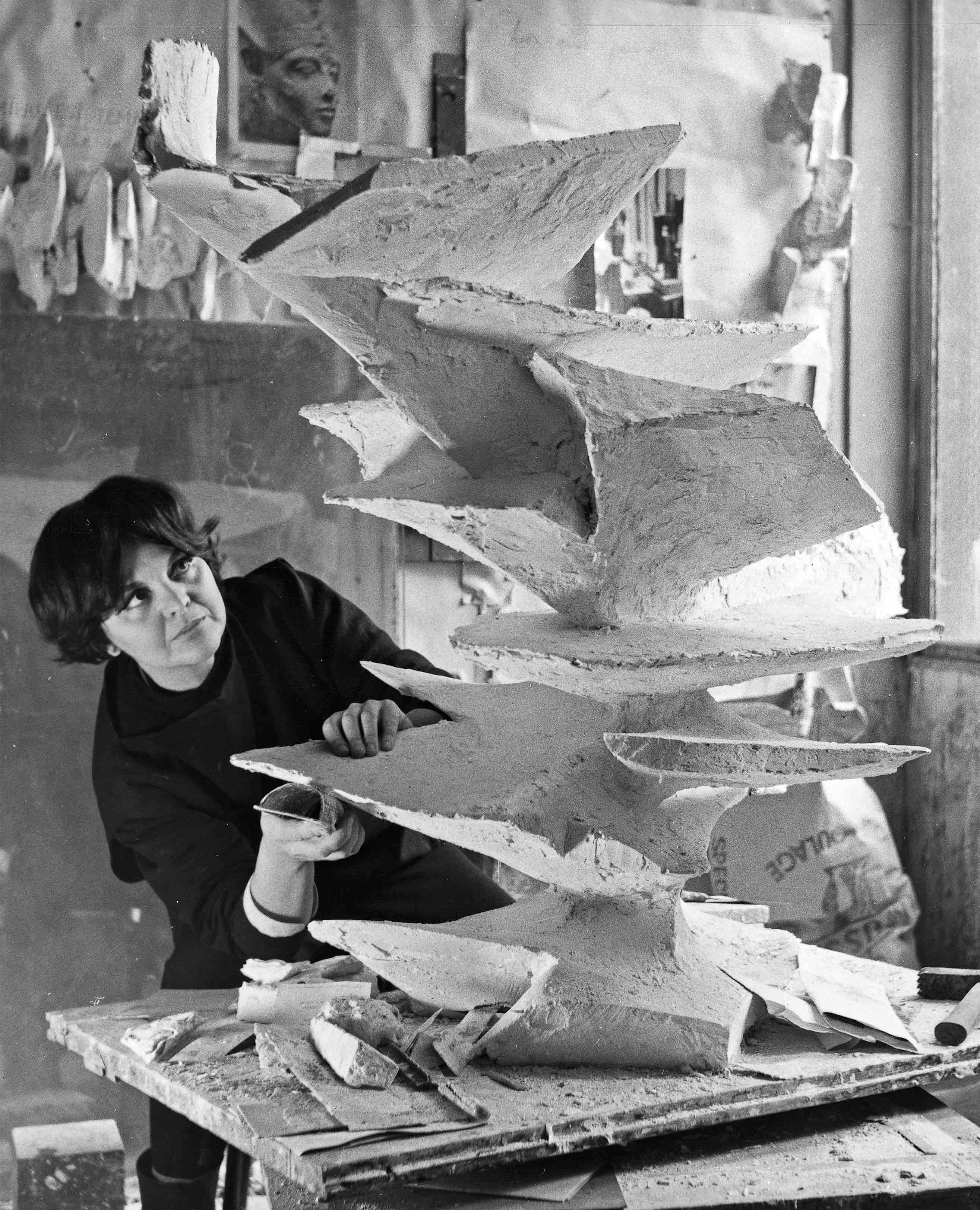

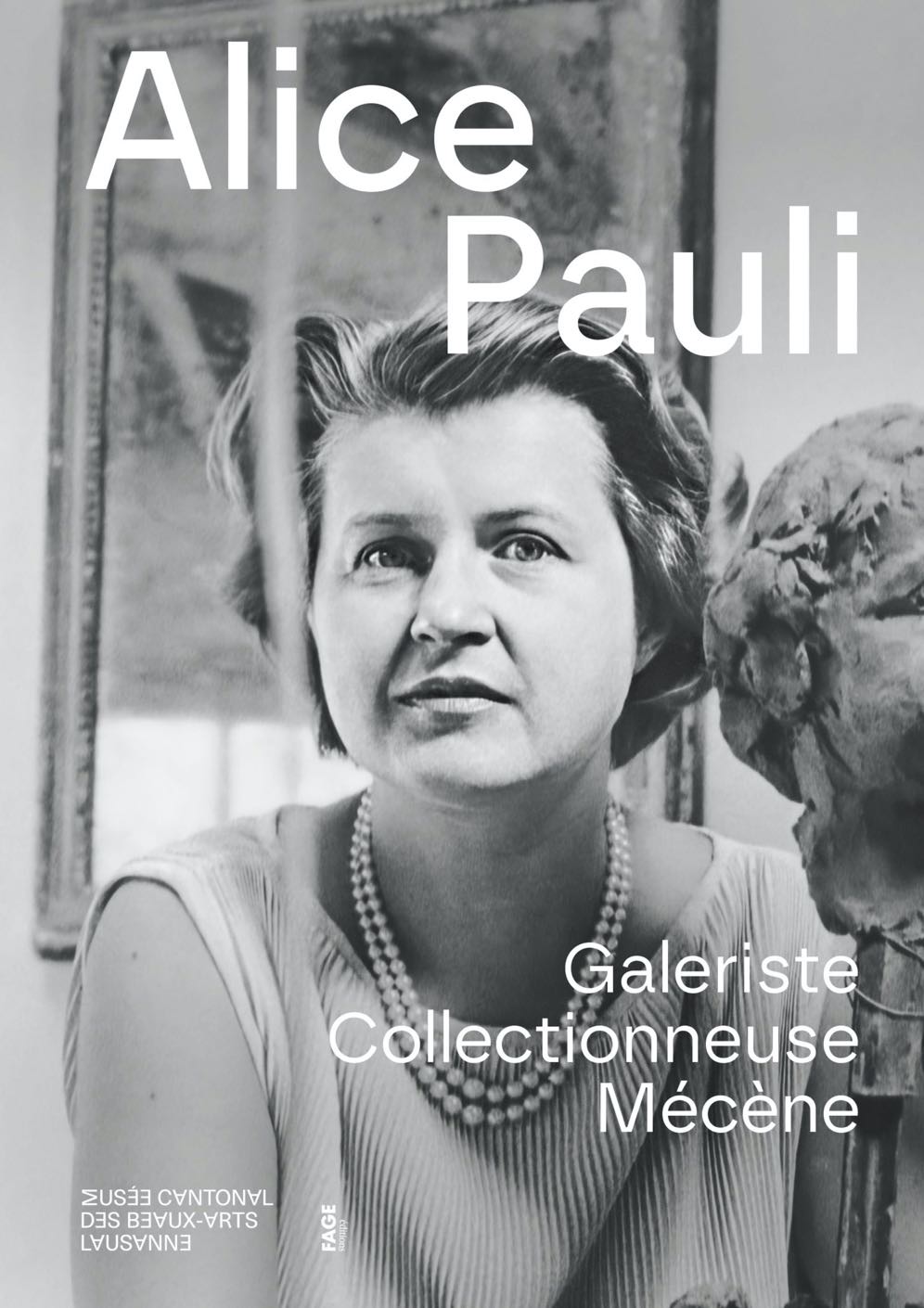

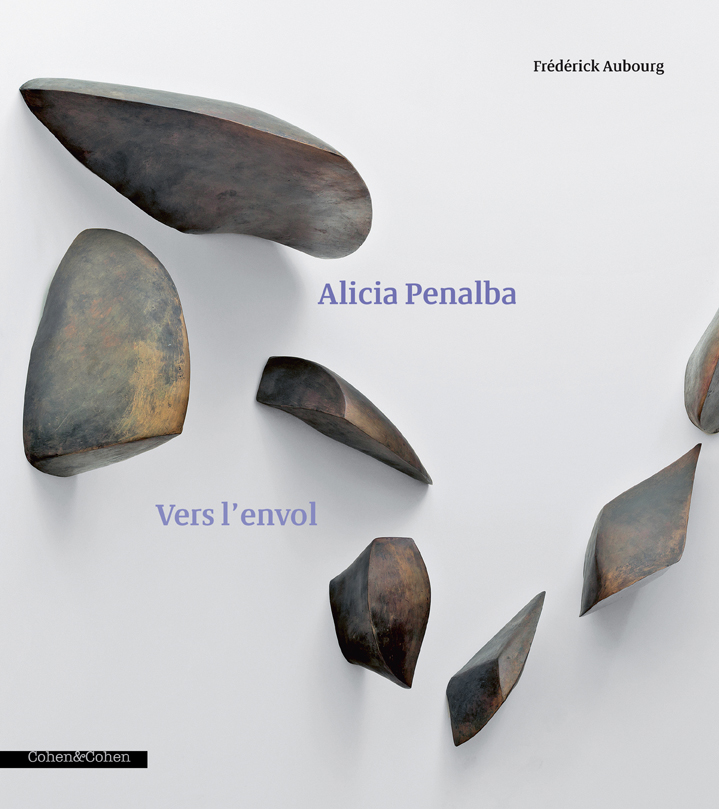

At the end of the 1950s, the series of Ailées consecrated a break up of vertical rhythms and the conquest of horizontality, with its elements superimposed in a fragile balance of layers, allowing the light to penetrate to the heart of the work. The spectacular Grande Imanta (1962), which was exhibited in 1967 during her first solo exhibition at the Alice Pauli gallery, bears witness to this development.

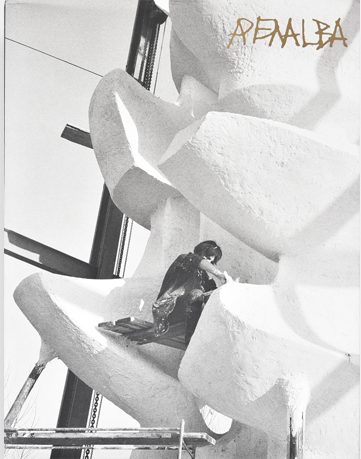

Constantly enriching her practice, receiving commissions which allowed her to express herself in vast spaces, Penalba tackled monumentality. The rhythms multiplied in the form of a dialogue with space, as evidenced by Forêt noire (1958), or Petit dialogue (1961), which prefigured her plans for water mirrors, like the one she designed for the headquarters of the pharmaceutical company Roche in 1971.

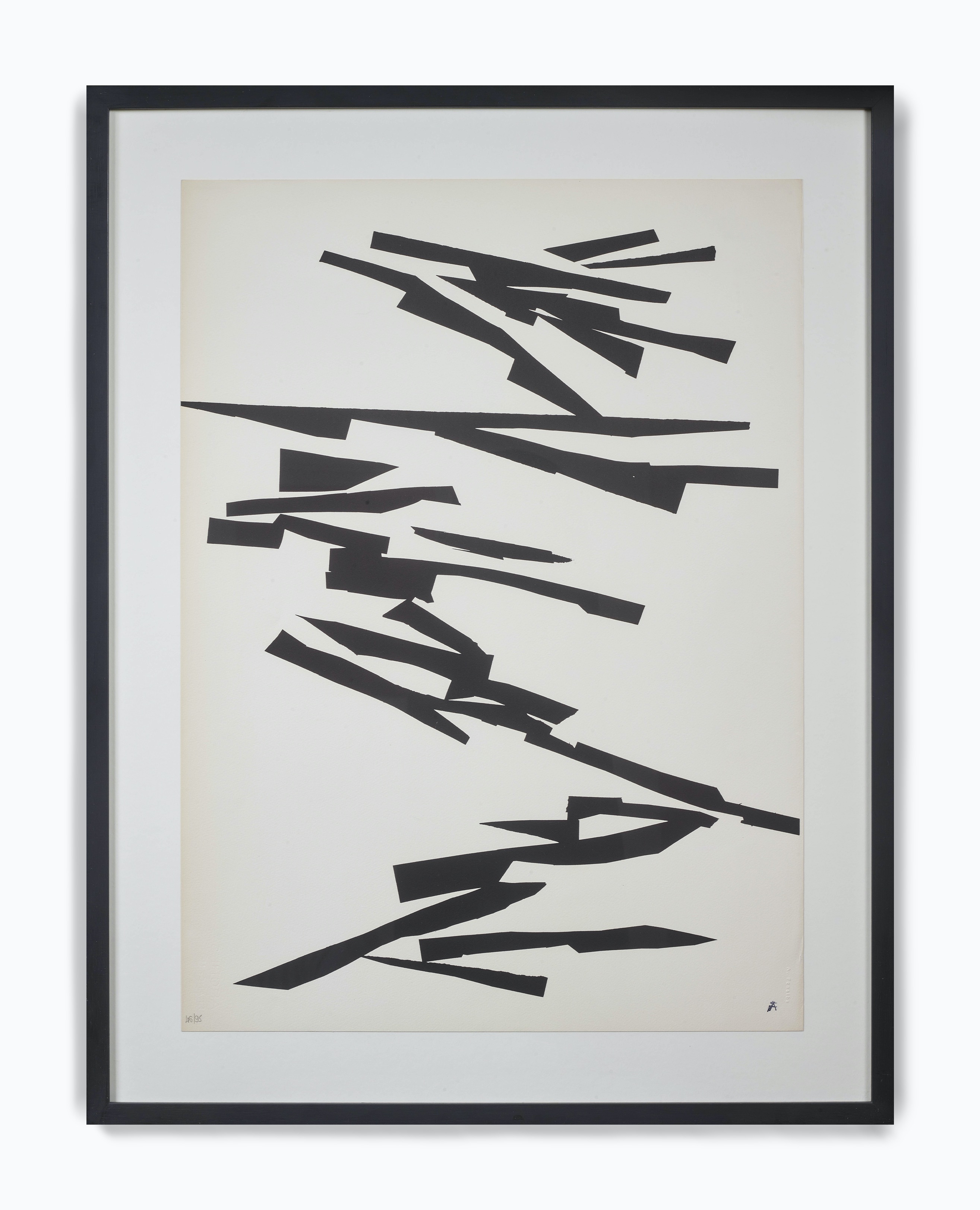

In a final development of her practice, Penalba set out to conquer walls. As if to better capture the flight of her sculptures, Penalba created autonomous wall reliefs, such as Amants multiples (1960), which dialogue freely with space.

Alicia Penalba’s life ended tragically in 1982 in a car accident.

Her creations were already held in many collections around the world, such as the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, the Centre Georges Pompidou, the Rijksmuseum Kröller-Müller in Otterlo, the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes in Buenos Aires and the Phillips Collection in Washington D.C. Alicia Penalba’s works are also visible today in spaces that commissioned her monumental works, such as the Pierre Gianadda Foundation in Matigny, Switzerland, or the Business College in St Gallen, Switzerland.