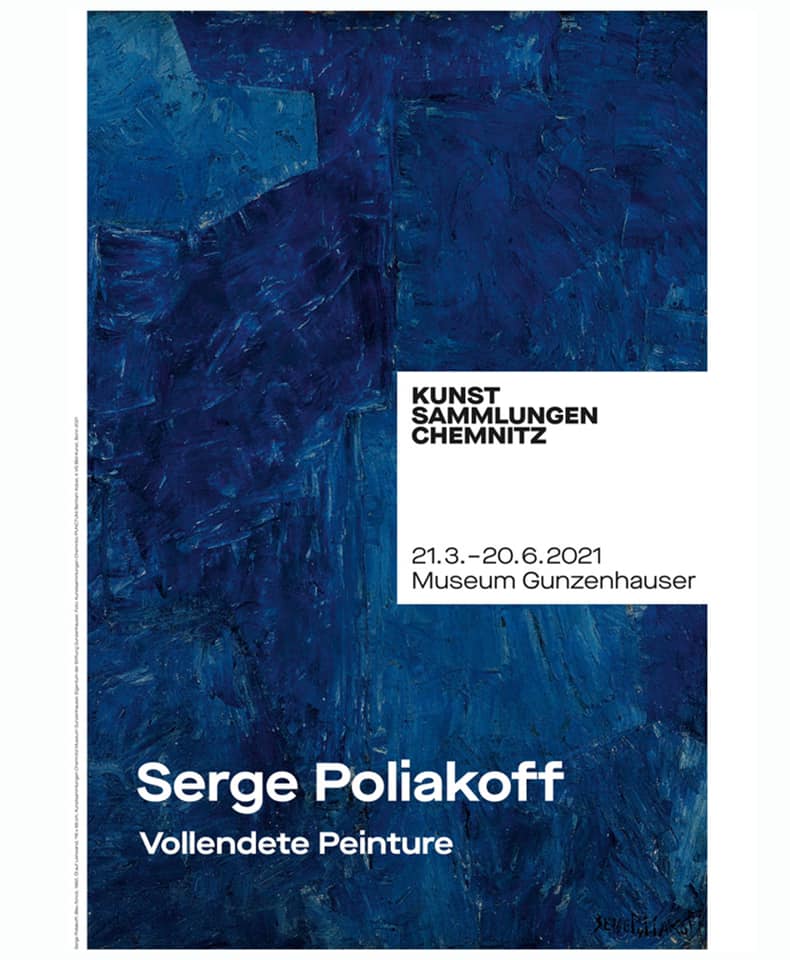

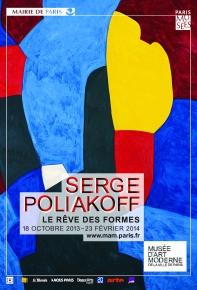

Born in Russia, painter Serge Poliakoff was one of the major figures of the School of Paris, to whom we owe a renewal of abstraction in the post-war period. His compositions, composed of interlocking free shapes and superimposed large coloured areas, reflect his research on the intensity of colour, the balance of construction, and the effects of the vibration and transparency of matter; “Transparency gives life,” the artist said. Over the course of more than three decades of work dedicated to pure abstraction, Poliakoff explored on numerous mediums: canvases, papers, lithographs, or even theater sets.

The artist’s biographers like to recount the romantic life of the man, born in Moscow in 1900, who, after he fled the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, wandered from Constantinople to London before settling in Paris. For a long time, he there lived a bohemian life, playing the guitar in Russian cabarets; it is not insignificant to recall this long journey, to emphasise that Poliakoff’s success came late and that it took him a good twenty years to gain recognition as a painter, after many years of training in various art academies, including that of the Grande Chaumière.

Some encounters were decisive in leading Poliakoff to abstraction. In 1937, the year the Bauhaus closed, he discovered Vassily Kandinsky, who had settled in Paris four years earlier. Although he did not retain everything of his pictorial approach, his meeting with the great Master of Abstraction marked a turning point in his life and encouraged him to pursue his own path. Through the Delaunay couple, whom he frequented regularly from 1938, Poliakoff was then introduced to the theory of simultaneous contrasts. But it was probably with Otto Freundlich, whom he met the same year, that he felt the closest. This great humanist’s compositions in fragmented chromatic planes, his sensitivity, and his search for balance between form and colour made a great impression on him.

These encounters and the progressive evolution of Poliakoff’s painting towards pure abstraction echoed the visual shocks that gave his pictorial approach an almost mystical dimension. In the lingering memory of the Russian churches that his mother showed him as a child, there remained a fascination for the mysterious, severe beauty of religious icons, the partitioning of their colours and the juxtaposition of spaces. Later, during a visit of the British Museum, he discovered the Egyptian sarcophagi. Scraping the surface of one of them, he uncovered the layering of matter, revealing the effects of transparency and vibration produced by this process. Decisive impressions and fundamental lessons succeeded each other, from which Poliakoff drew an eternal body of work.

This work, identifiable at a glance, is anchored in a continuous dialogue between pure form and colour. This formal language, taken for itself, stands as the living, vibrant matter that Poliakoff, as the great architect that he is, used to construct unique compositions, guided by a constant search for the interconnected balance of forms. Beyond this technique, the originality of Poliakoff’s work lies in its sensual and meditative dimension. It invites calmness, silence, and contemplation, and often, eludes analysis.

In 1945, his first solo exhibition at the Galerie l’Esquisse paved the way for international recognition. Eight years later, in 1953, his solo show at the Circle & Square Gallery in New York allowed him to win over the American public. In 1962, as he was granted French nationality, a whole room was dedicated to his work at the Venice Biennale. He was awarded the Kandinsky Prize in 1947, then the Tokyo Biennale prize in 1965. His first major retrospective took place shortly after his death, in 1970, at the Musée d’Art Moderne in Paris. Today, Poliakoff’s works are preserved in the collections of numerous prestigious museums, including the Tate Gallery, the Centre Pompidou, the MoMA, and the Kunstmuseum Bern.